Muslims in Europe

Open Discussions in association with Gulf Cultural Club

to mark the 30th anniversary of this programme

(May 1994- May 2024)

Muslims in Europe

*Tharik Hussain

(Author, travel writer, journalist)

**Professor Humayun Ansari

(Academic, author)

*** Karen Dabrowska

(Author, Journalist )

Tuesda 14th May 2024

Islam is the second-largest religion in Europe after Christianity. Although the majority of Muslim communities in Western Europe formed recently, there are centuries-old Muslim communities in the Balkans, Baltic, Caucasus, Crimea, Mediterranean and Volga region. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, large numbers of Muslims immigrated to Western Europe. By 2010, an estimated 44 million Muslims were living in Europe including an estimated 19 million in the EU. But like the Muslim presence in Spain, Portugal and Italy, Europe’s Muslim history and heritage is almost never mentioned and tends to be remembered negatively when it is remembered at all despite the region’s fourteen centuries of Muslim history and its huge indigenous Muslim population. Whilst much evidence of the historical presence can be seen in countries like Spain and Portugal, some of the best places to go looking for the living indigenous presence and heritage are in what is often termed ‘Eastern’ Europe, where Muslims have lived for almost six centuries, largely as part of the Ottoman Empire. As a result three of these countries still have Muslim majority populations: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Albania are effectively Europe’s only ‘Muslim’ countries. Meanwhile others like Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia and Montenegro also remain home to long established native Muslim communities.

Chairman: Salam Aleikum. It is now the 30th anniversary of this programme so now I am old and decrepit. In the next 30 years I won’t be here and the challenge for our community is to keep the programme going. We have to think about our legacy. Hopefully the younger people will come and take over the reins.

I will just say a few words about the venue here. I grew up in the UK in the 60s. My father came to the UK in 1963 and we followed in 1966. There were very few activities related to the community. This was a group of immigrants who were really foreign and alien in this country. They travelled from different backgrounds. My father was teaching English to the English.

Other immigrants came to different parts of the UK: Leeds, Bradford and Sheffield. But then the community grew up and centres were set up in London and outside London.

Before the programme in Abrar House the Muslim Students’ Association was set up in the 60s by the students who were living in London from Iraq, Bahrain and Kuwait. I remember when I was very young my father chaired a programme organised by Dr Saeed’s older brother. There were many other people involved.

That was in 1967 and there were community activities and other immigrants came from Iran and Lebanon where there was a civil war taking place. And then the community grew up. Then Open Discussions started on different topics and we had numerous speakers.

In line with these discussions there was a disclaimer that you would find in financial circles in their brochures that whatever happened in the past does not reflect the future. And here what is said on the rostrum does not reflect what Abrar House stands for. I think that is very important. In Open Discussions everybody is allowed to speak their mind.

Tharik Hussain: The question is is there really a Muslim Europe? I am going to explore Europe’s indigenous Muslim presence by taking you on as journey which I undertook for my latest book.

indigenous Muslim presence by taking you on as journey which I undertook for my latest book.

Muslim Europe is at least 15 centuries old. We now see an image from Iberia which is from inside the Al Hamra.

The culture and the Islamic civilisation were great achievers and a largely tolerant society existed. Europe’s Muslims and its Jews experienced a golden age the pinnacle of which was in 929 AD when a descendant of Muawiya declared himself the caliph. So we have here what you might call seven centuries of indigenous Muslim Europe.

But Muslims and Jews were kicked out of the Iberian Peninsula. So for my book Minarets in the Mountains, a journey through Muslim Europe my family and I went on a journey in search of Europe’s indigenous Muslims and the route we took took us through six countries. Three of them are Muslim countries Bosnia Herzegovina, Kosovo and Albania are Muslim in population like my country of birth Bangladesh.

And yet the idea of European Muslim countries today is some kind of oxymoron.

I took along with me a Turkish traveller/writer Evliya Çelebi who travelled through this region when it was as Muslim as it would ever be. And that is why I took him with me. From this journey I revealed the ttangible and intangible heritage of Muslim Europe. There are some important themes from the book before I offer my conclusions.

So we start here in Mostar. This is the stary mosque. It is not the original. I am sure you are all aware that the original was completely destroyed during what was considered an act of cultural genocide to remove the Islamic identity from the region. But it was recreated. So the 16th century bridge was built by the great Turkish Muslim architect Mimar Hayruddin.

Durin my research I began to appreciate just how Islamophobic historical literature has been. So the English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in 1897 wrote : “there is no way that these barbarians could create something so beautiful.” He said this was a marvellous remnant of Latin civilisation in the midst of Turkish barbarity.

When I was writing this book it was nuggets like this that made it apparent to me why Muslim Europe was being so easily dismissed. Although this bridge was destroyed it evokes the spirit of local Muslims. When the bridge was destroyed the UN was lobbied and they reconstructed it – six months ahead of schedule.

In Mostar we have this gorgeous 14th century lodge. Today it is used by the Sufi order.

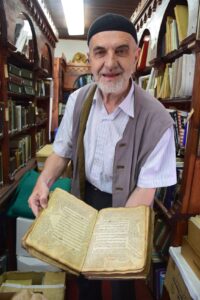

Now we have this gentleman holding a piece of Muslim heritage. It is a very rare book of Hanafi and Shafi and I am told it is older than Sarajevo. To find it in this non descript library where my friend grew up shows how much of this tangible heritage is still there and how much of it may have disappeared because of the way in which it was destroyed.

Now I take you to Macedonia. It is on the border with Albania. My two daughters were desperate for burgers and my wife noticed a painted mosque. I was completely blown away. Although I had seen this art in the region it was one of the finest examples. And for me it epitomizes an art style that is very rarely spoken about.

Here European and Islamic influences really come together. You can see the classic Islamic with the baroque rococo. It was termed the Julian style in around the 18th century. For me it is European/Muslim art. It is very indigenous as well.

Now we come to the twin town of Sarajevo. I was emotionally brought to my knees being a very well weathered traveller. Three is a magical number in Islam. The man did not want my money he wanted dawa. It was in this forgotten town in Western Serbia they were preserving this wonderful tradition of caring for the musaki.

While we are on this pictorial journey I bring you to another Serbian town just around the corner. It was a very different place. I could not even establish if it had any Islamic heritage. Chelabi told me that during his time it had been predominantly Musli and there were mosques everywhere and now there was one decrepit mosque and half a minaret.

It was while trying to discover this Islamic heritage that I followed the town’s Ottomans trial. It was not called the Ottoman trial. It was called the revolt against the Turkish oppressors . I ended up in front of a synagogue. It was a Sephardic synagogue despite its modern design. If I did not know my history I would have just dismissed it like every other person who was on the trial.

The only reason there are Sephardic Jews in the Balkans was that when the Jews of Spain were kicked out of Iberia an entire naval fleet was sent to collect these refugees and take him to his land. Of course many of them went to North Africa.

If you the connect the two phases of Muslim Europe we have twelve centuries of European Islamic history where for 12 centuries the safest places in Europe for the continents most persecuted religious group was in Muslim lands.

I was very angry. This is not part of my understanding of European history. Nobody talks about it and it made me very upset. Given what is going on it made me realise how different the world was.

So I am going to end now by leaving you with this quote from the great travel writer Tim Mackintosh Smith: “Europe has long turned a blind eye or, worse, looked askance, at its own Islamic self – the Muslims of the Balkans. Tharik Hussain opens our eyes to this vivid, varied and still vital Muslim presence …”

Maybe there is no Muslim Europe because Europe has never really come to terms with its own Muslim self.”

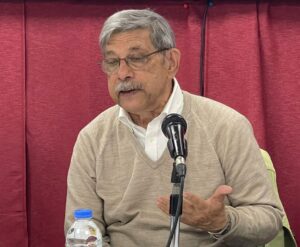

Humayun Ansari: Two dominant perceptions of British Muslims have endured in wider British society: First, that Muslims lack roots in British soil; this perception calls into question their emotional ties, loyalties and claims of belonging to Britain as their homeland. Despite contributing so much to British society to the common good, British Muslims still tend to be viewed as a huge problem. A ‘radical’ minority of Muslims is often seen as broadly representing the whole of the British Muslim community – a community that is inaccurately portrayed as undifferentiated, isolationist, opposed to modern norms and values, and immune to processes of change.

First, that Muslims lack roots in British soil; this perception calls into question their emotional ties, loyalties and claims of belonging to Britain as their homeland. Despite contributing so much to British society to the common good, British Muslims still tend to be viewed as a huge problem. A ‘radical’ minority of Muslims is often seen as broadly representing the whole of the British Muslim community – a community that is inaccurately portrayed as undifferentiated, isolationist, opposed to modern norms and values, and immune to processes of change.

What we see here is a mismatch between how non-Muslims often perceive Muslims and how British Muslims typically perceive themselves. A recent survey showed that Muslims actually identify with Britishness more than any other Britons: more Muslims are proud to be a British citizen compared to the general public; more Muslims want to live in diverse and mixed neighbourhoods compared to non-Muslim Britons.

By contrast, Muslims, often associated by wider society with extremism and violence, are the UK’s second ‘least liked’ group, after Gypsy and Irish Travellers.

Between April 2022 and March 2023 there were 3,400 hate crimes committed against Muslims in England and Wales; 995 Islamophobic hate crimes in London alone. All very challenging!

England cricket player, Moeen Ali’s experiences summed up the challenges involved. As he put it when speaking about his English grandmother, Betty Cox: “Nobody could believe it … when people look at me and think of my origins they would never think I have a family tree which is a bridge between England and Pakistan.”

Another perception that persists in Britain today despite concrete evidence to the contrary is that Islam is an alien religion; that it arrived only recently and so possesses no deep historical and organic links with the customs, traditions and values of British society such as those claimed for Christianity and even Judaism.

Again, this view belies historical scrutiny and in doing so denies British Muslims rootedness and legitimacy in Britain as their homeland.

So, what is this history? Well, contrary to popular perceptions, the relationship between Muslims and the British Isles goes back close to the beginning of Islam.

A gold dinar, in the British Museum, bearing Qur’anic verses referring to the fundamentals of the Islamic faith along with the name of 8th century King Offa of Mercia suggests awareness of and commercial interaction with the so-called Muslim world as early as the eighth century. Then with Muslim rule firmly established in Granada and Cordoba, there is sporadic evidence of Muslim visits to English shores, increasing further after the so-called Crusades.

Then, in 1453, the Ottomans conquered Constantinople and became an acknowledged power on the European stage. Elizabeth I in 1588 offered alliance to Sultan Murad, ‘a fellow monotheist’ to bring about the downfall of the ‘idolatrous’ King of Spain. From this period onwards, a range of commercial, political and military interactions developed, bringing Muslim sailors and traders to England.

Ottoman ambassadors arrived accompanied by their staff and servants as did Muslim adventurers and scholars.

Sake Deen Mohammed accompanied Captain Baker of the East India Regiment in 1784. He eloped with and married a ‘pretty’ Irish girl from a ‘respectable family’. In 1810 he opened the first ever Indian restaurant in London, then settled in fashionable Brighton, establishing his shampooing and herbal vapour baths business; a roaring success; King George IV was one his clients.

A trickle of elite Muslims, especially those closely associated with the British authorities arrived – their exotic lifestyles and forms of dress, stirring the popular imagination in England.

Returning East India Company officials brought back servants and ayahs. Unfortunately, many were mistreated; others discharged and left destitute.

A clear exception to this pattern was Munshi Abdul Karim – who arrived from India soon after the Golden Jubilee in 1887 as a ‘courtier’ to Queen Victoria who became deeply attached to him.

Another particularly significant group arriving in Britain during the nineteenth century was maritime workers on East India Company ships. Treated brutally many regularly ‘jumped ship’, settling in port cities. There they were joined by Yemeni and Somali seamen particularly after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

The First and Second World Wars triggered further Muslim migration to replace British labouring men called up for war duty and acute shortage of labour in the 1950s.

So, as we have seen, the Muslims who settled in Britain in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries represented a sizeable but highly differentiated population in ethnic and class terms.

Indeed, the most striking aspect associated with Muslims living in Britain today is the diversity that they represent. This is clearly reflected in the wide range of distinct cultures, languages and political traditions that we find around us – South Asian, Middle Eastern, African, and indeed European.

An interesting development in late 19th century Britain was the emergence of indigenous Muslims. Some Britons with more intimate engagement with Muslims and Muslim societies arrived at a decidedly positive evaluations of Islam – regarding it as a progressive moral force – and in some cases they converted. One of the most prominent of these converts was William [Abdullah] Quilliam, a reputable solicitor from the Isle of Mann.

After his conversion in 1887 he set up the Liverpool Muslim Institute [LMI] and began to organise a Muslim community around it. In the media he was immediately denounced as a lunatic. His system of religious belief was pronounced as ‘un-English Eastern humbug’. His congregation became the target of mob violence.

In this Islamophobic climate Quilliam’s task of propagating Islam became extremely challenging. How then did he go about it? To his largely Protestant audiences, he emphasised the continuity between Christianity and Islam. He built bridges with interested local people by adopting a form of ritual to which they were accustomed and with which they felt at home: morning and evening services were organised on Sundays where hymns, many taken from Christian evangelists but adapted by Quilliam to be ‘suitable for English-speaking Muslim congregations’, and accompanied by the organ, were sung. In these ways Quilliam sought to construct an indigenous, British, Islamic tradition.

Interwar Muslims too could prove to be equally accommodating in their social behaviour.

The Woking Mission, an initiative set up at the Shah Jahan Mosque in 1913 by an Indian barrister, Khwaja Kamaluddin, adopted a staunchly ecumenical approach – the entire spectrum of Muslim denominations was welcome; he took pains to display flexibility and patience regarding observance of rituals by new Muslims who strove to give up values and habits that had played a central role in their pre-Muslim lives.

Leading converts, such as, Lady Evelyn (Zainab) Cobbold the first British woman to perform Hajj, Marmaduke Pickthall, the ‘translator’ of the holy Quran, and Sir Archibald Hamilton, a Deputy Surgeon General in the Royal Navy, encouraged and facilitated social and cultural intermingling, especially through such bodies as the British Muslim Society (est. 1914).

Much of these Muslims’ activities were conducted with a light touch in a convivial atmosphere with due regard for the social etiquette, conventions and customs, modes of conduct and practices current at the time. Hence, festivities were celebrated at prestigious hotels and restaurants. ‘At Homes’ became a regular feature of their religious intercourse.

At one such occasion, for instance, Maulvi Inayat Khan, the well-known interwar sufi Muslim, presented a rendition of Indian classical music on the sitar and a number of English women followed suit with recitals on the piano and violin.

Ideas about Islam were thus presented in ways that suggested that it could be relevant to the British environment. Purdah in the British environment, for instance, was deemed to be quite impracticable. Public gatherings were generally mixed affairs, as were the religious festivals and the larger congregations. Music was deemed to be a fine art and outside the confines of religion it could be ‘a real blessing for humanity’.

I have been focussing on pioneering Muslims and leading individual converts and their activities. Let me now return albeit briefly to the communities of poorer classes of Muslims that had become established in Britain’s ports and industrial centres by the end of the Second World War.

Poorer Muslims approached life pragmatically. When, for instance, they felt that their needs were in conflict with tradition governing such matters as social and sexual relations, they were willing to alter their practices sufficiently to allow them to achieve workable compromises with their new cultural and economic environment.

The narrative I have constructed so far enables us now to identify and reflect on a number of comparisons between the situation of British Muslims today and those who were present before the second half of the twentieth century – we see similarities as well as differences.

The demographics do look very different: from a few thousand a hundred years ago, British Muslims now form a faith community of around 3.87 million or 6.5% of the total.

It remains a fact too that, as before, the majority of British Muslims (particularly first-generation arrivals) remain concentrated in semi-skilled or unskilled jobs, living in multiply deprived and relatively overcrowded and under-resourced inner-city neighbourhoods; that their average rate of unemployment is much higher than that of the broader population.

But, despite these challenges, British Muslims continue to defy stereotypes and instead respond with a sense of optimism. Sizeable numbers of Muslims now live in affluent suburbia; they proliferate the professions. Currently there are well over ten thousand Muslim millionaires in Britain with liquid assets of tens of billions of pounds.

Their contribution to the public sphere and government is accelerating – c.50 Peers and Members of the current Parliament, with women in the majority.

They represent a range of religious interpretations and practices. Some are devout, others merely nominal. Diasporic living has generated innovative critical thinking. Thanks to the internet’s availability of the diversity of Islamic perspectives and marginalised Muslim voices, especially women, some are increasingly challenging the hegemony of traditional authority and re-examining issues of power and ‘othering’ within their religion, asking sensitive questions.

For instance, challenging traditional views, as far back as 2008, Amina Wadud delivered the khutbah and led Friday prayers in Oxford.

Ditto, Raheel Raza in 2010.

This brings me lastly back to consider the lingering perception that British Muslims find ‘integration’ with modern Britain difficult.

A little while ago a newspaper article entitled ‘One Day In The Life Of Muslim Britain’ described how a selection of Muslims spent a Friday – a ‘normal’ working day.

One was, Rear Admiral Amjad Hussain (retired), Head of the Royal Navy’s defence logistics; He spent the day on meetings in Whitehall with other admirals, a sandwich lunch at the Liberal Club with the commander-in-chief of the Navy, discussing a contract for tugs and boats, and a Trafalgar Night dinner on HMS Victory before being taken home in Hertfordshire. As he put it, ‘I have developed my moral code according to my religion … I pray when I have time, but my day is not driven by it.’

Or take this collection of prominent British Muslims – a dynamic and productive fusion of Muslim and British cultures. Very few of them, if any, fit stereotypes commonly associated with Islam. For them, while there may have been challenges, there was nothing particularly incompatible about their Islam and modern Britain.

Chairman: I now call on Dr Saeed Shehabi to say a few words about the Gulf Cultural Club and the Open Discussions programme.

Dr Saeed Shehabi: It has been a pleasure to work with you all. We were young then. We had so much activism in us. Shabir was with us and Fatima Dosa. It is an honour to be a bridge between us all. We wanted to exchange our culture and views and thoughts. This is the only way. We can either go to war or we can have peaceful interaction and this is what we have chosen. We have chosen to have peaceful interaction between all of us.

And luckily Allah has helped us. We cannot claim to have achieved everything we wanted but definitely we have established a tradition where we meet once every month and debate various topics: East-West relations, Islam and the West, the GCC, the EU and the Arab world and so on and so forth. There are many topics and issues that we have discussed. We had prominent speakers from academia, Muslim authors and scholars. We have managed to do that during the past three decades. The hope is that we can continue to do this.

Fatima Dosa: Can I give you my story. Saeed started the lectures in 1994.I joined ten years. I am from Kenya. Post 9/11 I was the victim of an Islamophobic attack. But it had a positive effect. Now I have a much straighter nose.

When I was the victim of an Islamophobic attack and coming from a very diverse, integrated country Kenya where we were from different religions and different races but we never saw each other as the other. When I came to Britain the so called land of milk and honey during my university days I asked myself why in London with such a diverse history that Muslims were seen as the other and what could I do to change that.

I was able to explore different cultures. I came to this organization. I have always been an activist but it was only of late in Dr Saeed Shehabi that I found somebody who never questioned my choice of speakers or topics. He allowed me a free hand. He could see the vision long term and did not pull me back but allowed me to move forward.

I thank him 20 years on that we have moved from strength to strength and I thank Karen and Shabir for being with me on this journey. Karen for her talk and for capturing what we do here. So the discussions will not be lost. They are there for future generations.

Shabir Rizvi: Any other forum like this would celebrate in an even bigger way. We have had speakers like John Snow from Channel 4, Ken Livingstone, Jeremy Corbyn, George Galloway. Fatima Dosa helped to organize the lectures and cajoled and twisted the arms of the speakers to come and give their valuable time. We now need someone to take the reins and I think that is very important.

Jaffar Al Hasabi: The first lecture I attended was in 1995. This is the first one. I was always taking care of the technical issues since that time until now and I will continue with it.

Karen Dabrowska: Thariq Hussain presented an excellent overview of Muslims in Europe. Professor Ansari narrowed the focus to Muslims in Britain and I will narrow the focus even more with a walk through London’s Muslim heritage. But before doing that we have to say something about Open Discussions.

Ansari narrowed the focus to Muslims in Britain and I will narrow the focus even more with a walk through London’s Muslim heritage. But before doing that we have to say something about Open Discussions.

Today we celebrate an anniversary. In May 1994, 30 years ago Saeed Shehabi inaugurated the first open discussions programme at the Gulf Cultural Club. The speaker was Fred Halliday and the topic was the civil war in Yemen when the south tried unsuccessfully to break away from the north and re establish the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen. Thirty years later we are still speaking about Yemen the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. We are honoured by the presence of Tariq Hussain and Professor Ansari. It has been an absolute pleasure working with you both to organize tonight’s discussion.

Concerned about the absence of a discussion forum to focus on the Middle East and Islamic Affairs where people from the Middle East and North African region and anyone interested in that part of the world could meet to exchange views Open Discussions began holding monthly meetings. Then and now Saeed’s aim is to build bridges of understanding and foster co-operation.

If we wanted to mention all the eminent speakers who have addressed Open Discussions we would be here until midnight so let me start with some of the dear friends and colleagues who have passed on: Professor George Joffe, Lord Avebury, Lord Ria, Lord Ahmed, Lord Patel of Blackburn, Bert Mapp author of Leave Well Alone about the West’s fraught relationship with Gulf States, and Ahmed Aziz director general of Bank of Iran.

Politics have been extensively discussed: Islam and the West, the Arab spring, the Crisis in Yemen, troubled states like Afghanistan and so on. But emphasis has also been given to religious and inter faith topics and every year there is a discussion about Ramadan and celebration of Christmas. Our topics on religious subjects have been compiled in this book: A spiritual journey with the Abrar Islamic Foundation.

The meetings have been addressed on a number of occasions by Jeremy Cobyn, Chris Doyle from CAABU, Professor Charles Tripp from SOAS, Roger Hardy from the BBC, Dr Abdelwahab El-Affendi, well known journalist Tim Llewlyn and Saudi academic Dr Madawi Al Rasheed and hundreds of other speakers. Regular attendees have included the Saudi ambassador Turki Al Faisal, diplomats, political activists, human rights defenders and people from all walks of life interested in the MENA region.

Above all Saeed has to be admired for his constancy, dedication, tireless enthusiasm and effort to make sure we have a lecture every month. I remember once someone came to Saeed’s office with a very ambitious programme. As always Saeed heard him out and thanked him for his suggestions. He then remarked that we have to be mindful of our resources and work within our means. This is why the GCC and Open Discussions have been with us for 30 years.

Time is marching on so let me briefly talk about London’s Muslim Heritage with a focus on tourist sites. This talk should be given my Abdul Malik Tailor of Halal Tours who has organized more than ten excellent walks around London of special interest to Muslims. Unfortunately he is not able to be with us here today. I have been on many of these walks and would like to share a few insights.

When south-eastern Britain was overrun by the troops of the Roman emperor Claudius in A.D. 43 the city has 10,000 Muslim residents.

Just outside temple underground station we have Templars church from where the knights departed for the crusades in the Holy Land. In nearby Fleet Street The Black Muslim Times was set up by the first black Muslim editor Duse Mohamed Ali at no 158.The Ottoman Empire was not keen on the printing press but a Muslim convert persuaded the sultan to change his mind and some of the first printed copies of the Quran came from the presses of Fleet Street.

In the Old Bailey court dating from 1539 sailors from the Indian Ocean region known as lascars who included Yeminis were tried for theft. They were paid a pittance and sometimes had to steal to survive.

A Turkish bathhouse just outside Liverpool Street station which was built in 1895 is now an upmarket venue for special events, banquets, weddings and feasts.

Lets move now to the heart of London and the National Portrait Gallery where there are many interesting works. From Ottoman times we have a painting of Sultan Hamid II. There is also a photograph from 1867 of Hafiz Abdel Karim who rose to become Queen Victoria’s personal tutor and taught HRH Urdu.

We than come to Trafalgar Square where one of the reliefs on Nelson’s column shows Nelson after the Battle of the Nile in 1798 in Egypt where he is wearing a Muslim Crescent.

In 1600 Abdul Al-Walid bin Masud the Moroccan ambassador lived on the Strand. His primary task was to promote the establishment of an Anglo-Moroccan alliance and he spent six months at the court trying, unsuccessfully, to negotiate an alliance against Spain. During his time in London he watched jousting and became a well known figure on whom Shakespeare is said to have based the character of Apollo the Moor in the play Othello which was performed in the Banqueting Hall.

In front of the houses of parliament is a statue of Cromwell (1599 – 1658) an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of the British Isles. Cromwell wrote a letter to the ruler of Algeria requesting the release of prisoners. That’s when pirates were very active on the North African barbary coast.

Parliament Green opposite the House of Commons has been hosting Open Iftar. Since 2013, people from all walks of life have come together to break fast, share food and engage in inspiring conversations.

In Kingsway Hall on December 6th 1949 Mohammed Ali Jinnah gave a speech in which the word Pakistan was used for the first time. Eight months after that speech the state of Pakistan was established.

In 1890 on the Strand the Lyceum Theatre wanted to stage a play about Prophet Mohammed but was prevented from doing so because of the intervention of Sultan Abdulhamid II.

Professor Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner a Professor at King’s college in the Strand commissioned a mosque to be built in Woking for his Muslim students in 1889

Ten days before his assassination in 1965 Malcolm X gave a lecture at the LSE which now has a very active Middle East Institute also with a lecture programme like Open Discussions.

In Bloomsbury the British Museum is a treasure trove of Islamic history and artefacts. housed in the Albukhary Foundation Gallery.

London university’s SOAS, is dedicated to the study of the languages, cultures and societies of Africa, Asia and the Middle East, and is the only higher education institution in Europe with this academic specialisation.

London’s first mosque was established in 1895 in Camden Town by Hadji Mohammad Dollie.

When the Vauxhall Pleasure Garden was in its heyday it was often visited by Yusuf Agâh Efendi, a Tripoli-born son of a nobleman chosen by Sultan Selim III on 23 July 1793 as the first resident Turkish ambassador to Britain.

In Whitechapel is the famous east London mosque and Altab Ali Park named after Altab Ali, a 25-year-old Bangladeshi Sylheti clothing worker murdered on 4 May 1978 by three teenage boys. The 70s were a bleak time in London with many racist attacks that came to characterise the East End at that time. Today Brick Lane with numerous Indian restaurants run by Bangladeshis and many retro shops is a thriving multicultural neighbourhood and major tourist attraction.

When Westfield a massive shopping complex in Ariel Way with 300 shops and 60 restaurants all under one roof was being built a Caribbean convert to Islam Abdul Karim suggested the setting up of a multi faith centre with a prayer room which would be used by the Muslims who live and work in the area. This would be good for business as the Muslims would also visit the shops and restaurants in the area. His suggestion was well received and he was even given the opportunity to visit the top of Westfield when it was still under construction. The prayer room is modern and convenient, with sofas and separate men/women ablution facilities.

In Walthamstow a building in Chelmsford Road has had a number of incarnations. It started life as church, then became a synagogue was finally converted into the Masjid Al Umar at a cost of £2.5 million

In Avenue Road off Gunnersbury Lane in Acton Yusef Ali translated the Quran into English. Ali was an Indian-British barrister who wrote a number of books about Islam. A supporter of the British war effort during World War 1 he received the CBE in 1917.

This is just a short snap shot of the Muslim history of London. In sha Allah a short book Historic Walks through Muslim London will be published in the not to distant future. Thank you.

*Tharik Hussain is an award-winning author, travel writer and journalist specializing in Muslim heritage and culture. He is a Fellow at the Royal Geographical Society in London and the Centre of Religion and Heritage at the University of Groningen. Tharik’s book, Minarets in the Mountains; A Journey into Muslim Europe, won the British Guild of Travel Writers’ Adele Evans Award for best travel narrative book of 2022. Tharik is also the author of several travel guides for Lonely Planet, including Saudi Arabia (shortlisted for the 2020 Travel Media Awards), Bahrain, Thailand, London and Great Britain. He has written about encountering Muslim cultures and heritage across the globe for various media publications from National Geographic Traveller to the BBC. In July 2019, Tharik created Britain’s first Muslim heritage trails, in Surrey, England; in 2017 he was named one of the UK’s most inspiring British Bangladeshis and in 2016 his BBC World Service radio documentary, America’s Mosques; a story of integration, won Best Religious Program at the New York Festivals World’s Best Radio Programs Awards.

**Professor Humayun Ansari is Professor of Islam and Cultural Diversity at Royal

Holloway University of London. He is a historian of Islam and cultural diversity, with a focus on Muslims living in the West. His book The Infidel Within: Muslims in Britain Since 1800 (first published in 2004) pioneered the historical study of the experiences of Muslims living in the United Kingdom. His academic publications have explored ethnicity, identity, migration, multiculturalism and Islam in the West. He has also written about Islamism, Islamophobia, radical Islamic thought and Muslim youth identities. Since these themes are also of contemporary interest, his work has connected the university world with government, policymakers and local communities, underpinning consultancy and research projects. In 2002, he was awarded an OBE for services to higher education.

***Karen Dabrowska was born in New Zealand to Polish parents. She is a journalist and writer who previously worked as Director of Communications for Friends of South Yemen and Development Officer for the Sudanese National Council. Karen has worked as a journalist for the Evening Post a daily newspaper in New Zealand and, after immigrating to the United Kingdom as features editor and then editor of New Horizon – news and views from the Muslim world – magazine. She was also London correspondent for the Jana News Agency, assistant editor of Islamic Tourism magazine and edited several news letters about the Middle East. Her publications include Iraq: The Ancient Sites and Iraqi Kurdistan, The Libyan Revolution: Diary of Qadhafi’s Newsgirl in London, Into the Abyss: Human Rights Violations in Bahrain; Iraq: Then and Now, Iraq The ancient sites and Iraqi Kurdistan and Mohammed Makiya A Modern Architect Renewing Islamic Tradition.